Oh boy. This turned out to be a monster of a post. Please try to bear with us, and not posting tl;dr would also be appreciated.

Up until now, the three of us writing here have all been working and writing separately, but this time we’re working together. Today we want to talk about choice systems in video games, with a focus on the popular ‘moral choice’ systems. We chose this topic after playing through inFamous a little while back. I’ve beaten inFamous on the good path, Shoofle has beaten it on the evil path, and Maggie has finished the good path and is working through the evil path now. Also, since we’re working together on this, the use of “I” at any point in this article could be referring to any of us. So try not to get too confused.

A word of warning, there will be a few minor spoilers for some games. We avoided all the big spoilers, but just letting you know.

First off, what makes a choice system a choice system? After all, every game offers the player choices in some matter or other. In platformers, you can choose whether or not to collect power-ups, in shooters you pick which guns to use, in RPG’s you pick which skills to develop or which party members to use, in strategy games you pick which units to use and when to send them where. But these kinds of things aren’t what come to mind when we think ‘player choice’. So for the purpose of this discussion, we have to first define what a choice system is. The rather simple definition that I’m going with (at least for the purpose of this discussion) is this:

A game has a choice system if the player must explicitly make a decision that affects the story.

By explicitly I mean the game essentially stops you and goes “Do you want to pick this option or that one?”, and then the story continues based on your choice. Making the decision is mandatory, most of the time there’s no way to avoid or miss it. This obviously rules out games with completely linear stories, and also rules out a lot of games with multiple endings like Chrono Trigger, where many of the alternate endings are obtained by finding a (usually) hidden way to fight the final boss early, or some of the Castlevania games, where the ending you get depends on whether you equip various items during the ‘final’ boss fight. Going by this definition then, a game with a moral choice system is simply where the choices the player makes involves choosing between good and evil.

Next, what are some games with choice systems, moral or not? Rather than launch straight into a tirade about what we think about choice in general, we’re going to first talk about some games that have featured choice systems, and our thoughts on how those games implemented them.

Next, what are some games with choice systems, moral or not? Rather than launch straight into a tirade about what we think about choice in general, we’re going to first talk about some games that have featured choice systems, and our thoughts on how those games implemented them.

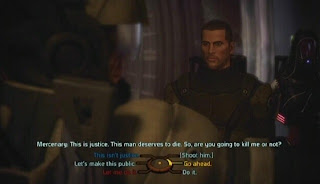

|

| Dialogue options in Mass Effect |

The Mass Effect series has extensive branching dialogue, and a Paragon/Renegade alignment system. The alignment system works well but is often too black and white within the game. There are many moments where the paragon/renegade choice boils down to simplistic morality, such as having to choose between good and evil (to kill or spare a character for example), and most of the major decisions you have to make throughout the series have paragon/renegade point values assigned to them. However, despite mostly offering stark black and white for its choices, the alignment system works well at providing a spectrum for defining the character of Commander Shepard, whether each player’s Shepard is more diplomatic or confrontational, etc. Most importantly, there is never a need to play strictly paragon or renegade, though of course you can if you want (this is more true for the second game than the first). The player is free to choose the option that they think suits them best. And what is most interesting for Mass Effect is that all of the decisions, big or little, carry through the games, so a decision made in the first game can come back to haunt (or help) you in the 3rd. The potential for branching storylines is immense, and one can only imagine how difficult it must be to take all of the threads from the first two games and tie it all together in the third, not to mention that there will undoubtedly be more important decisions to make in the third game (unless you work at Bioware, in which case you know exactly how hard it is).

The Infamous series is one of those with a strict morality system, and although they’re excellent games overall, the morality system stands out as somewhat subpar. It has a tendency to beat you over the head with an overly dramatic choice between “good” and “evil.” The joke we’ve been tossing around for a while now is “Do I save these orphans or kick this puppy?” - always spoken in the overdramatic, deep, gravely voice of Cole McGrath. One of the earliest decisions in the game is “Should I tell him that his wife is dead and see if he’ll let me through or should I just kill him?” The game goes into sepia tone as Cole ponders - with much sandpaper-voiced deliberation - which action to take, and, just in case you what was going on, a shiny karmic choice symbol flashes in the corner. Beyond the simple problems in presentation, the really irritating thing is the lack of any reward for the middle ground - in fact, the outright punishment for anything less than Mother Theresa-like conduct or Hitleresque misconduct. In order to get the best powers, you need to play the game as strictly good or strictly evil, and a platinum trophy requires a playthrough on each. Whenever a good or evil side mission is completed, the other one in the area is “locked out,” further emphasizing the strict duality of the morality system. The story itself barely changes depending on whether you play as good or evil, with the sole exception being one mission near the end that has a more significant choice. Apparently Infamous 2 has major sections of the game that are restricted to one path or the other (none of us have had the chance to actually play yet), which is definitely a step in the right direction, even though it does retain the strict black and white morality system.

Another game with a poor morality system is Bioshock. As with Infamous, Bioshock is a great game overall (at least, from what I’ve played of it), but features a clumsy morality system. Throughout the game, the player can encounter and fight Big Daddies, who are each guarding a Little Sister - a young, defenseless girl. Upon defeating the Big Daddy, the player has the option of either harvesting (thereby killing) the Little Sister for a large amount of ADAM (used by the player to obtain new abilities and upgrades), or saving her life for less ADAM. Hopefully, you can tell which is the good choice and which is evil. This choice has no major impact on the story, and only affects which of the two (or technically three) endings the player sees.

While none of us have played much of it, Dragon Age: Origins poses many questions to the player. The most obvious choice given to the player is that of their origin story, as players have six different choices, each adding its own variances to the story. I (Maggie) am currently playing as an Elven mage, and so had to begin with my “Harrowing,” the rite to graduate from apprentice to mage by defeating a demon in the Fade. This lends an interesting depth to each character, and gave me different conversation options with another mage later in the game, but the story proceeds the same once the origin stories are linked. What I have liked so far is that the questions posed seem real and there is frequently no “right” choice. [MINOR SPOILERS] My favorite example so far happened when I encountered a small boy possessed by a demon. My choices were to kill the boy and the demon alongside it, allow the boy’s mother to sacrifice herself to a forbidden blood magic rite to put me in the Fade so I could kill the demon without killing the boy, or I could go to the Circle of Magi for help and risk that in the time I take for the journey, the demon may destroy the town. I sat at that screen for ages trying to decide, since I’d stumbled across the conversation and hadn’t saved recently enough to try the other branches. My eventual choice was the blood rite, and one of my fellow characters disapproved. [END SPOILERS] These choices appear to have little impact on the overarching story (though, like I said, I’ve completed only a few quests), but the fact that they do not follow strict good and evil morality makes them have more impact. Between the origin story and my character’s realistic choices, I have felt more immersed in this than any other RPG I’ve played.

On the topic of immersion in RPGs and difficult choices, The Witcher 2 is by far one of the best examples of a choice system in video games. The Witcher 2 shuns black and white morality, and the entire world is steeped in shades of moral grey. I’m barely a few hours into the game, yet already several sidequests have shown me just how difficult it is to be ‘good’ in the Witcher, and the most recent sidequest I’ve attempted has literally made me stop playing for a while to consider my options and basically think through the arguments for and against capital punishment before making a decision. Something about the Witcher 2 just makes it feel more important, which (added to the lack of simplistic morality) makes every choice more interesting.

The Infamous series is one of those with a strict morality system, and although they’re excellent games overall, the morality system stands out as somewhat subpar. It has a tendency to beat you over the head with an overly dramatic choice between “good” and “evil.” The joke we’ve been tossing around for a while now is “Do I save these orphans or kick this puppy?” - always spoken in the overdramatic, deep, gravely voice of Cole McGrath. One of the earliest decisions in the game is “Should I tell him that his wife is dead and see if he’ll let me through or should I just kill him?” The game goes into sepia tone as Cole ponders - with much sandpaper-voiced deliberation - which action to take, and, just in case you what was going on, a shiny karmic choice symbol flashes in the corner. Beyond the simple problems in presentation, the really irritating thing is the lack of any reward for the middle ground - in fact, the outright punishment for anything less than Mother Theresa-like conduct or Hitleresque misconduct. In order to get the best powers, you need to play the game as strictly good or strictly evil, and a platinum trophy requires a playthrough on each. Whenever a good or evil side mission is completed, the other one in the area is “locked out,” further emphasizing the strict duality of the morality system. The story itself barely changes depending on whether you play as good or evil, with the sole exception being one mission near the end that has a more significant choice. Apparently Infamous 2 has major sections of the game that are restricted to one path or the other (none of us have had the chance to actually play yet), which is definitely a step in the right direction, even though it does retain the strict black and white morality system.

|

| Bioshock's 'choice' |

While none of us have played much of it, Dragon Age: Origins poses many questions to the player. The most obvious choice given to the player is that of their origin story, as players have six different choices, each adding its own variances to the story. I (Maggie) am currently playing as an Elven mage, and so had to begin with my “Harrowing,” the rite to graduate from apprentice to mage by defeating a demon in the Fade. This lends an interesting depth to each character, and gave me different conversation options with another mage later in the game, but the story proceeds the same once the origin stories are linked. What I have liked so far is that the questions posed seem real and there is frequently no “right” choice. [MINOR SPOILERS] My favorite example so far happened when I encountered a small boy possessed by a demon. My choices were to kill the boy and the demon alongside it, allow the boy’s mother to sacrifice herself to a forbidden blood magic rite to put me in the Fade so I could kill the demon without killing the boy, or I could go to the Circle of Magi for help and risk that in the time I take for the journey, the demon may destroy the town. I sat at that screen for ages trying to decide, since I’d stumbled across the conversation and hadn’t saved recently enough to try the other branches. My eventual choice was the blood rite, and one of my fellow characters disapproved. [END SPOILERS] These choices appear to have little impact on the overarching story (though, like I said, I’ve completed only a few quests), but the fact that they do not follow strict good and evil morality makes them have more impact. Between the origin story and my character’s realistic choices, I have felt more immersed in this than any other RPG I’ve played.

On the topic of immersion in RPGs and difficult choices, The Witcher 2 is by far one of the best examples of a choice system in video games. The Witcher 2 shuns black and white morality, and the entire world is steeped in shades of moral grey. I’m barely a few hours into the game, yet already several sidequests have shown me just how difficult it is to be ‘good’ in the Witcher, and the most recent sidequest I’ve attempted has literally made me stop playing for a while to consider my options and basically think through the arguments for and against capital punishment before making a decision. Something about the Witcher 2 just makes it feel more important, which (added to the lack of simplistic morality) makes every choice more interesting.

Now that we’ve described a few choice systems and our general thoughts on them, let’s backtrack a little. Why should a game use a choice system, morality or otherwise? The most basic answer is to increase the replay value - with multiple paths to be explored, the lifetime of the game is effectively increased with potentially less work for the developer, as conversations and environments can be recycled. A good choice system can also increase the immersion, such as with Dragon Age or the Witcher. Especially in an RPG, with a heavy focus on building and identifying with the character, a choice system can give more depth and control for the player’s character. Another thing is that choice systems are fundamentally linked to the defining difference between gaming and other media - interactivity. Games are essentially defined, for better and worse, by being in some way interactive. A game without any interaction is a movie. A good choice system makes the player’s role even deeper, changing from an actor with a set script to a living character within the game world. A video game might not have as much interaction as a tabletop RPG, where the game master can react to the player’s actions and improvise, but with some work it can come close.

So, if choice systems expand games so well, why haven’t more developers used them? The single easiest answer is that they’re bloody hard to implement. Any story with multiple branches is going to get out of hand very fast, especially if the branches are significant and occur early in the game. This quickly creates more work for the developers than is feasible on a normal project scale. The easy solutions are to simplify the system or cut it out entirely, which has resulted in mostly poor implementations of what could be a fantastic gaming instrument.

Keeping in mind the troubles that developers run into as well as our preliminary comments about games, let’s take a closer look at the pitfalls of choice systems, particularly when they’re based on morality. A lot of simplified systems suffer from lack of impact, such as in inFamous, where the story is only minimally affected by choices. This really hurts the sense of immersion and occasionally leads to gameplay being disconnected from the story. In inFamous, the evil choices typically revolve around you acting selfishly instead of for the greater good, which leads to some grating inconsistencies between the character and his actions, particularly regarding Zeke and Trish (the cloying good-for-nothing best friend and the girlfriend, respectively). Fable also has a morality system that doesn’t greatly affect the story (though Fable 3 looks like it may change that for the better), and while the options presented at the end of Fable 2 do offer a selfish reward for the player, it’s still hard to justify saving the world when my actions during gameplay show that I want to kill everyone anyway.

This isn’t even really purely related to choice systems, the conflict between gameplay and narrative exists in all games. For example, while it doesn’t feature a choice system by our definition, Red Dead Redemption features an open world allowing great freedom to the player outside of story missions, and perfectly showcases the clash between giving players more options in the gameplay and maintaining narrative coherency. Red Dead Redemption is about achieving (unsurprisingly) redemption as John Marston seeks to make up for the crimes he committed in his past by bringing his outlaw buddies to justice. He even insists on remaining faithful to his wife. However, you can avoid story missions and go on homicidal rampages in the world with virtually no consequence, which directly contradict the main story and make it lose a lot of impact or character development. The same goes for the Uncharted series, which really doesn’t offer players much freedom or choice at all. Uncharted pits Nathan Drake against various evil characters in a race to reach some legendary artifact first. Drake is portrayed as the good guy, kind, witty, good looking, etc, but practically every minute in the games where he doesn’t spend climbing around things, he spends killing everybody he encounters. Clearly this is a problem for all of gaming, not just choice systems. But having a poorly implemented choice system can often exacerbate the problem, or at least make it more obvious.

Now that we’ve presented games as examples, looked at the issues developers face, and griped about the current state of choice systems in games, here we present our suggestions to the world. Immersion and realism is the strongest point, and in contribution to that we’d like to see more systems based on choices other than good or evil. These moral systems simply aren’t very interesting. Even if the system avoids the infamous InFamous pitfall (forcing the player to be entirely good or entirely evil to get the benefits from either), a choice between good or evil is rarely interesting - and certainly hasn’t been yet. The player generally knows the outcome beforehand, and almost never need to actually think about the choice they’re making, because the options presented make it easy to say “I’ll go with this one because I’m doing a good playthrough, and then I’ll do an evil playthrough and choose that one.” These choices do not make one think - they are obvious and players (at least, in our experience) nearly unilaterally have essentially made all their choices before even picking up the controller. The choice takes you out of the game rather than pulling you in. This is especially bad when you know the outcomes, or you know how your abilities and such will depend on your choice. The question stops being “do I want my player to be good or bad” and becomes “do I want to experience the game from the good or evil standpoint”.

A choice that does not have an obvious outcome associated with the options forces the player to think about what the options mean - and forcing the player to think about the world is how to pull them in. For example, as an alternative to good/evil, lawful/chaotic can pose much more interesting questions. Loyalty to family, friends, and country can be tested. Choices that stand on shaky moral ground or propose an “evil” action in order to accomplish good are the type that will make players stop and question. In order to save your best friend, you must betray your country, cause, or morals. You are given orders to kill a man you believe is innocent. Conversely, you are given orders to protect a guilty man, perhaps one who killed your friends and family. These questions will not only give gamers more opportunity to stop and think when confronted with these difficult situations, they will lend themselves to deeper, richer stories that explore human nature in a way that other media cannot touch. It is one thing to watch characters in books or movies make decisions like this and entirely another to make these decisions yourself, knowing that it will impact the world of the game.

Further, these choices must impact the game, and there must be pros and cons for every choice. If there is a distinct “best ending”, and it is not prohibitively difficult to achieve, then you are doing it wrong. In real life, things rarely go so simply, and people would turn to walkthroughs to find which option will lead them through safely. That’s like facing Scylla, Charybdis, and a wide, marked-off safe channel between them: do I risk the seven headed monster and lose at least that many men, do I take the chance that we can sail out of the whirlpool, or do I just sail between them without a care in the world? It’s an insult to call that a choice. For developers to take advantage of the realism that a choice system can provide, there have to be realistic consequences.

|

| Infamous: An example of a poorly implemented choice system |

Keeping in mind the troubles that developers run into as well as our preliminary comments about games, let’s take a closer look at the pitfalls of choice systems, particularly when they’re based on morality. A lot of simplified systems suffer from lack of impact, such as in inFamous, where the story is only minimally affected by choices. This really hurts the sense of immersion and occasionally leads to gameplay being disconnected from the story. In inFamous, the evil choices typically revolve around you acting selfishly instead of for the greater good, which leads to some grating inconsistencies between the character and his actions, particularly regarding Zeke and Trish (the cloying good-for-nothing best friend and the girlfriend, respectively). Fable also has a morality system that doesn’t greatly affect the story (though Fable 3 looks like it may change that for the better), and while the options presented at the end of Fable 2 do offer a selfish reward for the player, it’s still hard to justify saving the world when my actions during gameplay show that I want to kill everyone anyway.

|

| This is not what people normally think of when they think about redemption |

Now that we’ve presented games as examples, looked at the issues developers face, and griped about the current state of choice systems in games, here we present our suggestions to the world. Immersion and realism is the strongest point, and in contribution to that we’d like to see more systems based on choices other than good or evil. These moral systems simply aren’t very interesting. Even if the system avoids the infamous InFamous pitfall (forcing the player to be entirely good or entirely evil to get the benefits from either), a choice between good or evil is rarely interesting - and certainly hasn’t been yet. The player generally knows the outcome beforehand, and almost never need to actually think about the choice they’re making, because the options presented make it easy to say “I’ll go with this one because I’m doing a good playthrough, and then I’ll do an evil playthrough and choose that one.” These choices do not make one think - they are obvious and players (at least, in our experience) nearly unilaterally have essentially made all their choices before even picking up the controller. The choice takes you out of the game rather than pulling you in. This is especially bad when you know the outcomes, or you know how your abilities and such will depend on your choice. The question stops being “do I want my player to be good or bad” and becomes “do I want to experience the game from the good or evil standpoint”.

A choice that does not have an obvious outcome associated with the options forces the player to think about what the options mean - and forcing the player to think about the world is how to pull them in. For example, as an alternative to good/evil, lawful/chaotic can pose much more interesting questions. Loyalty to family, friends, and country can be tested. Choices that stand on shaky moral ground or propose an “evil” action in order to accomplish good are the type that will make players stop and question. In order to save your best friend, you must betray your country, cause, or morals. You are given orders to kill a man you believe is innocent. Conversely, you are given orders to protect a guilty man, perhaps one who killed your friends and family. These questions will not only give gamers more opportunity to stop and think when confronted with these difficult situations, they will lend themselves to deeper, richer stories that explore human nature in a way that other media cannot touch. It is one thing to watch characters in books or movies make decisions like this and entirely another to make these decisions yourself, knowing that it will impact the world of the game.

Further, these choices must impact the game, and there must be pros and cons for every choice. If there is a distinct “best ending”, and it is not prohibitively difficult to achieve, then you are doing it wrong. In real life, things rarely go so simply, and people would turn to walkthroughs to find which option will lead them through safely. That’s like facing Scylla, Charybdis, and a wide, marked-off safe channel between them: do I risk the seven headed monster and lose at least that many men, do I take the chance that we can sail out of the whirlpool, or do I just sail between them without a care in the world? It’s an insult to call that a choice. For developers to take advantage of the realism that a choice system can provide, there have to be realistic consequences.

|

| A paragon interrupt option in Mass Effect 2 |

Another small way that these moments can lend to immersion is not to make them obvious *cough inFamous cough* but rather work them into gameplay. Mass Effect and Dragon Age handle this reasonably well, where most of the decisions happen in conversation. The decision of whether or not to kill a man can be decided, not during a sepia-tone cutscene, but by either firing or lowering your weapon, or talking to the man instead. Mass Effect also allows players to interrupt conversations at moments to perform a paragon or renegade action. Games may need to indicate a choice in some way, but that indication should be worked into gameplay so that that player isn’t treated like an idiot.

Ideally, players should be able to influence story on a deeper level than what we have seen so far. In inFamous, the course of the game doesn’t change based on whether you are good or evil, which also leads to more redundant replay. I’m only playing it again as evil to get the trophies and because occasionally people explode when I hit them with lightning. When games have multiple endings, they often splinter in only the last scene, as in Deus Ex. What would it be like to play a game where you could wind up on opposite sides of a war based on your decisions? It would grant you a possibly different gaming experience than your friends and lend tremendous replay value as the course of the game is entirely changed.

As we mentioned earlier, good choice systems are very simply hard to write and program. The most realistic of our suggestions is a simple request for more ambiguous choices. It will take a very ambitious and clever group to write and develop a truly immersive, branching story. In writing this post, I’ve begun to wonder if indie developers are in the best position to push this gameplay element to the next level. A group working without the pressure of producers and the strict timelines of larger companies may be able to take enough time at the storyboard level to make a compelling story. Granted, they often suffer a lack of experience and resources, but it might only take one to make a splash before larger developers take note. On the other hand, indie developers may not have the time to spend on such a game, and it may come down to a larger developer or producer to take a chance on a game with a larger story. Either way, it is a pretty large risk for a developer of any size to take on, with a large time investment and without the guaranteed return of a well-established series. Here’s hoping somebody takes the leap and does it right.

Ideally, players should be able to influence story on a deeper level than what we have seen so far. In inFamous, the course of the game doesn’t change based on whether you are good or evil, which also leads to more redundant replay. I’m only playing it again as evil to get the trophies and because occasionally people explode when I hit them with lightning. When games have multiple endings, they often splinter in only the last scene, as in Deus Ex. What would it be like to play a game where you could wind up on opposite sides of a war based on your decisions? It would grant you a possibly different gaming experience than your friends and lend tremendous replay value as the course of the game is entirely changed.

|

| We want this... |

|

| ... not this. |

No comments:

Post a Comment